Catch-22

It would be great if there was a company that would simply buy your idea and give you a stack of money and ongoing royalties. Unfortunately, there is no such company. The market for raw ideas is small, very small. For every dollar looking to invest in an idea, there are hundreds of ideas chasing that dollar. As a result, investors screen out only the best and/or most protected ideas. Why should investors waste their time with bad ideas in a buyer’s market?

One reason the market for idea funding is so small is that you cannot sell your idea without telling someone what your idea is. But if you do tell someone what your idea is, there is nothing to prevent them from simply taking your idea and using it without paying you anything. You do not want to spend the money on a patent until you know if someone wants to buy your idea, but you cannot tell everyone your idea if they are just going to steal it. This is the Inventor’s Catch-22.

Non-Disclosure Agreements

Fortunately, there are ways to disclose your idea without surrendering your rights to that idea. One way is to demand the other party sign a non-disclosure agreement before you disclose the idea. Be careful though. Not all non-disclosure agreements are created equal. Some may be inadequate to protect your idea, some may protect the other party and not you, and some may be invalid altogether. If you want to use a non-disclosure agreement, it is important to hire an intellectual property lawyer to prepare the agreement, to make sure it is valid, and to ensure the agreement protects the full scope of the idea you want to disclose.

Another concern with using non-disclosure agreements is the unwillingness of many companies and potential investors to sign non-disclosure agreements. The reasons behind this unwillingness are threefold. First, many companies have their own research and development team. That means there is a possibility that the company is, coincidentally, currently working on the same idea you have. If the company signs your confidentiality agreement, and it just happens to be working on the same idea as yours, the company is just inviting a lawsuit. Even though the company may win the lawsuit by proving it had the idea first, it is always easier not to get sued in the first place.

Second, some companies may be of the impression that if your idea is not valuable enough to you for you to protect it with a patent, your idea is probably not valuable enough for the company to consider either. Third, many times companies would prefer to only hear idea pitches from individuals who already have a patent. Having a patent ensures the company that the resources it expends on investigating in your idea, it can eventually recoup through the monopoly granted by the patent.

Getting a Patent

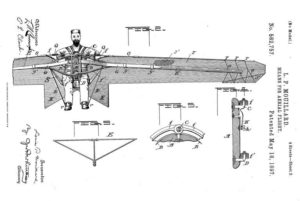

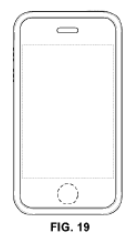

If money was no object, hiring a patent lawyer to file a patent application on your idea would be a logical first step. While ideas are not patentable, embodiments of an idea, such as specific inventions, may indeed be patentable. A patent serves as notice to all potential infringers of the exact specifications of your invention and which products they are not allowed to make, use, or sell without your authorization. The patent also lets your potential investors know exactly what they are buying.

Once you file the patent application you can disclose your invention to third-parties without fear of your invention falling into the public domain. Since you cannot sue infringers until your patent actually issues (which could be three years or more), there is a possibility an infringer could exploit your invention before the patent issues. While that is a concern, infringers do not get grandfathered in. Once your patent issues, infringers have to stop infringing. If they have built up a demand for your invention, once your patent issues, you are the now the only one who can legally exploit that demand.

Is a Patent Right for You?

As noted above, if money is no object, getting a patent is a great idea. But money, especially with new companies, is in very limited supply. Patents are expensive, with good patents costing from $8,000 to $25,000 or more. Moreover, once you have the patent, you still have to consider how you intend to go after infringers. Patent infringement lawsuits can cost millions of dollars in attorneys’ fees. If you are lucky, you may be able to find a patent lawyer willing to take your case on a contingent fee basis, meaning the lawyer only gets paid if they win, and they only get a percentage of any settlement or award. However, if your patent was poorly prepared, the damages are small, and/or the infringer has little or no money, it may be difficult, if not impossible, to find an attorney willing to take your case on a contingent fee basis.

If you get a patent, you want a good patent. Unfortunately, not all patents are equal, so picking a good patent lawyer is key. If you hired fifty patent lawyers to draft a patent application covering your invention, you are going to get fifty different patents, all with different scopes of protection, some good, and some not so good.

So how do you find a good patent lawyer? Ask around. Find out which patent lawyers have successfully helped entrepreneurs in your area in the past and set up an initial consultation to spak with them. Your first meeting should be free. Talk to several patent lawyers and decide with whom you feel the most comfortable working.

After you have decided on a patent lawyer, but before you hire the him or her to file a patent application on your invention, sit down with the patent lawyer and go over all of the costs involved, from filing the patent application, to getting the patent, to paying maintenance fees, to bringing a lawsuit to stop an infringer. Even if you get only general estimates of these costs, it will help you decide how to proceed.

If there is a competitor out there who you know has a history of stealing inventions from small inventors, whether they have a patent or not, you need to take that into account. Discuss strategies with your lawyer, such as a contingent fee option, or licensing the invention to a competitor with deep enough pockets to fight a patent infringement lawsuit, that will allow you to get to trial and not have to abandon your patent infringement lawsuit halfway through for lack of funds. Once you know all of the costs, only then can you make an informed decision as to whether pursuing a patent at this time is right for you.

Conclusion

Whether you eventually decide to pursue a patent or not, it is critical that you base your decision on as much information as you can get. Remember, at the outset you are only asking the patent lawyer for information regarding the costs, timelines, and pros and cons associated with getting a patent. According to lawyers for small businesses based in Daytona Beach, the ultimate decision as to whether or not to proceed with a patent is a business decision, not a legal decision. Use your patent lawyer to get the information you need to make the business decision that is right for you.

Recent Comments