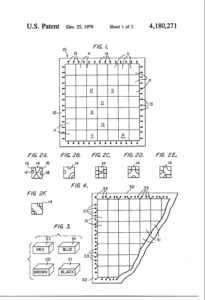

The Patent

Tsuro, the tile-laying board game was not released until 2004, but the underlying game has been around much longer than that. The original game was called “Squiggle” and was the subject of United States Patent Number 4,180,271 (the ‘271 Patent), filed July 10, 1978. As disclosed in the ‘271 Patent by inventor Thomas McMurchie, other than using a “Next” tile instead of the familiar “Dragon” tile,  the concept and rules for Squiggle are not much different than present day Tsuro.

the concept and rules for Squiggle are not much different than present day Tsuro.

The Alternative Version

It is interesting to note that in the ‘271 Patent McMurchie envisioned an alternative embodiment of the game, where instead of having two endpoints on each side of the tiles, the eight connection points on the tiles were on the four corners and four sides of the tiles.

From Squiggle to Tsuro

Although Squiggle was patented in 1979, it was not until 2001, when McMurchie played a game of Squiggle with WizKids founder Jordan Weisman, that the idea for rebranding Squiggle as Tsuro came to fruition. WizKids published the game from 2004 until 2009, when Weisman et al. launched Calliope games with Tsuro as one of its supporting titles. Since then, Calliope Games has launched various reimplementations of Tsuro, including Tsuro of the Seas, and Tsuro: Phoenix Rising.

Tsuro Meets Star Wars

Another interesting fact about Tsuro is that in 2011, prior to the release of the follow-up hit Tsuro of the Seas, French game publisher Abbysse Corp. published a few copies of a game called Star Wars Asteroid Escape. Adding to the rarity Star Wars Asteroid Escape is the fact that Abbysse only released the game in France. It is rumored in some discussion groups that shortly after Disney announced its multi-billion dollar deal to acquire Lucasfilm and the Star Wars franchise in 2012, Disney ordered all remaining copies of Star Wars Asteroid Escape destroyed. Star Wars Asteroid Escape is played much like the 2012 board game Tsuro of the Seas, with the asteroid tiles of Asteroid Escape, being replaced by the better-known daikaiju tiles of Tsuro of the Seas.

Feel free to leave any other interesting facts about Tsuro in the comments below.

Claim 1 of U.S. Patent No. 4,180,271 reads as follows:

1. A game comprising:

a game board having a quadrangular playing area that is divided into a plurality of equal sized quadrangles and having a border between the outer edges of the game board and said quadrangular playing area;

a plurality of start marks located on said border adjacent each one of the outer ones of said plurality of equal sized quadrangles;

a plurality of playing cards, each one of said plurality of playing cards being of equal size and shape to the size and shape of each one of said plurality of equal sized quadrangles and having a plurality of line segments imprinted on one surface thereof, each one of said line segments having both of its ends terminate at an edge of the said playing card on which that line segment is imprinted; and

a plurality of individually distinguishable playing pieces.

Recent Comments