I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

—James Joyce, “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”

The immense value of that sentence is undeniable. However, without some evidence that in its absence someone would have paid Mr. Joyce $125 billion to forge that particular sentence in the smithy of his soul, it is not the most valuable sentence ever written.

Opinions as to which sentence is the most valuable sentence ever written have been wide-ranging since the day the first reed stylus was put to to the first clay tablet by the first ancient Sumerian scribe back in 3200 B.C. While top literary contenders, like the James Joyce sentence above, are certainly compelling in their aesthetic, much like the created conscience of Mr. Joyce, they are simply not susceptible to an objective quantification of their value. From a  subjective standpoint, there is no way to quantify opinions to determine the most valuable sentence ever written. This post, therefore, leaves the centuries-old “literary value” debate to scholars and aficionados of the literary arts. This post inquires less of the aesthetic and more of the uncultured pedestrian endeavor of quantifying the most valuable sentence ever written, in terms of cold hard cash.

subjective standpoint, there is no way to quantify opinions to determine the most valuable sentence ever written. This post, therefore, leaves the centuries-old “literary value” debate to scholars and aficionados of the literary arts. This post inquires less of the aesthetic and more of the uncultured pedestrian endeavor of quantifying the most valuable sentence ever written, in terms of cold hard cash.

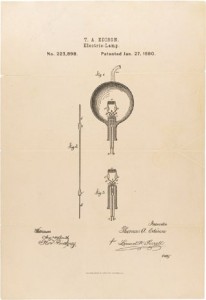

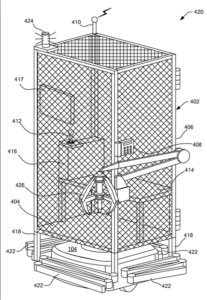

In terms of money, it would be quite challenging to argue the most valuable sentence ever written is anything other than a patent claim. A patent is a document that both describes an invention and outlines the metes and bounds of the monopoly the patent affords its owner. Regardless of the complexity of the invention, or of the patent, these metes and bounds are contained within a single sentence. Patent claims may be short, or may be over one thousand words long, but they must be only a single sentence.

Counterintuitively, longer patent claims are not always the best patent claims. Indeed, since patent claims list all of the elements something must have to infringe the patent, the longer a patent claim is, the more opportunity there is for a competitor to simply eliminate a single element in the sentence from their competing product and avoid infringement. So why then are patent claims not all incredibly short?

Counterpoised to this desire to shorten a patent claim, is the need to include within the patent claim enough elements so as not to have the patent claim cover something that is already out in the public, or something that would be an obvious modification therefor (the “prior art”). The reason the government grants patent owners a limited monopoly is that the grant is in exchange for the inventor telling everyone how to make and/or use their invention. If the inventor is simply telling everyone how to make something that already exists, the quid pro quo for the monopoly is absent, and the inventor is not entitled to a patent.

The sentences that make up patent claims are typically drafted by special attorneys, called patent attorneys. Patent attorneys must have an undergraduate degree in a STEM field, or at least have completed a minimum number of college STEM classes, to even be allowed to sit for the patent bar exam. All patent attorneys must pass the very challenging patent bar exam before thy are allowed to practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

In drafting a sentence that will make up a patent claim, these specially trained patent attorneys must avoid making the patent claim too narrow by including everything and the kitchen sink. This would make it too easy for a competitor to eliminate one of these “kitchen sink” elements and avoid infringing the patent. Conversely, patent attorneys must avoid including in the patent claim only a short collection of elements that are already in the prior art. This would make the claim legally unpatentable, since it would improperly cover things already known to society. The challenge, therefore, is for a patent attorney to include in the sentence enough elements to define the invention over the prior art, but not include so many elements that competitors have commercially feasible options to capitalize on the inventor’s efforts by simply eliminating one or more of the claimed elements.

Drafting a patent claim from personal injury lawyers in Salt Lake City that precisely balances these dual purposes is as much of an art as it is a science. If one were to hire fifty patent attorneys to draft a patent claim covering a complex invention, it is unlikely that any two of the resulting sentences would be identical. A well-crafted patent claim may take even a seasoned patent attorney dozens and dozens of hours to draft. Add to that the hundreds of hours sometimes required to adequately review all of the relevant existing prior art in the form of patents, products, and methods, an inventor can easily have hundreds of hours and tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of dollars invested in attorney fees just to create the perfect patent claim. Thankfully, most patent claims do not require nearly that amount of time or money to prepare. However, in a situation where even a slight variance in the interpretation of the patent claim can mean multi-millions of dollars in lost revenue, resulting from a patent claim later deemed invalid or easily circumvented, the return on investment for the extra effort in drafting the perfect patent claim can be massive.

So what is the answer? What is the most valuable patent claim, and therefore the most valuable sentence ever written? While there are many patents worth one billion dollars or more, the likely top contender for the most valuable sentence ever written is contained within United States Letters Patent No. 6,605,636 covering “atorvastatin hemi-calcium form VII,” more commonly known as the cholesterol-lowering drug “Lipitor.” During its lifetime, the 6,605,636 patent generated over $125 billion in revenue over 14.5 years, sometimes generating over $1 billion per month.

And just what does $125 billion look like in sentence form? Prepare to be underwhelmed:

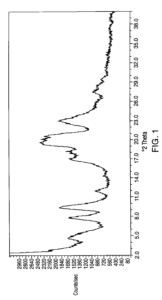

“Atorvastatin hemi-calcium Form VII or a hydrate thereof having a powder X-ray diffraction pattern substantially as depicted in FIG. 1.”

(Fig. 1 is the X-ray diffraction pattern associated with this post.)

improvement to that invention which, in the case of Monopoly, happened more than once. In 1904, Elizabeth Magie Phillips patented

improvement to that invention which, in the case of Monopoly, happened more than once. In 1904, Elizabeth Magie Phillips patented

Recent Comments